You’ve been watching the police crisis unfolding in the news this year. But where did it all begin?

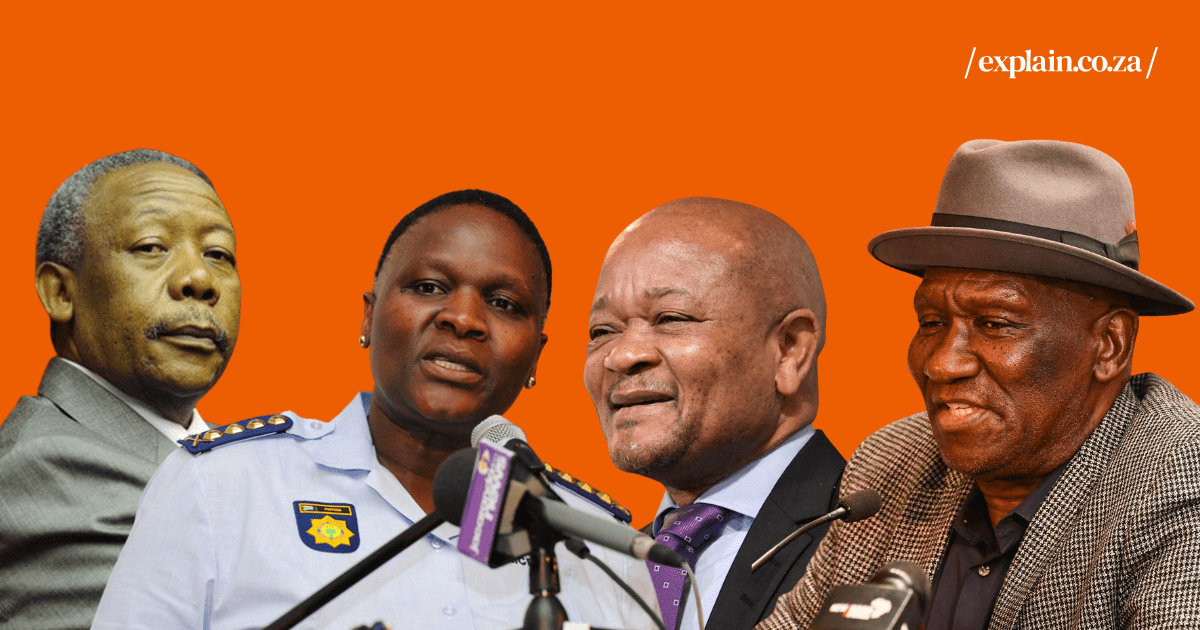

The team at explain has been breaking down the key players and allegations that have emerged in the Madlanga Commission and parliament’s parallel ad-hoc subcommittee.

Our police explainer series:

- What is the Madlanga Commission? Inside South Africa’s explosive justice inquiry

- The Madlanga Commission’s ‘Big Five’ crooks explained

- Senzo Mchunu to Shadrack Sibiya: The cops in the Madlanga Commission explained

Both are investigating the explosive allegations made by KwaZulu-Natal’s top cop, Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi, in July this year. He went public with allegations of criminal infiltration of our justice system, going all the way to the top, and that mess is currently being investigated in both inquiries.

But the fact is that the problems bedevilling the South African Police Services (SAPS) reach right back to the very beginning of modern-day South Africa – and beyond.

In this week’s explainer, we’re throwing it back to why SAPS finds itself in such a mess and how we can start to fix it.

Born from the brutality of apartheid, the South African Police Service was supposed to morph into a beacon of community safety after 1994. Instead, it has stumbled from one scandal to the next, leaving public confidence in tatters.

Think Jackie Selebi’s corruption bombshell, the blood-soaked fields of Marikana, and now, the fresh wounds of Minister Senzo Mchunu’s suspension amid whispers of ‘Big Five’ syndicate ties.

This is the roadmap to why reform keeps hitting a brick wall, and why today’s Madlanga Commission might be our best shot at real change.

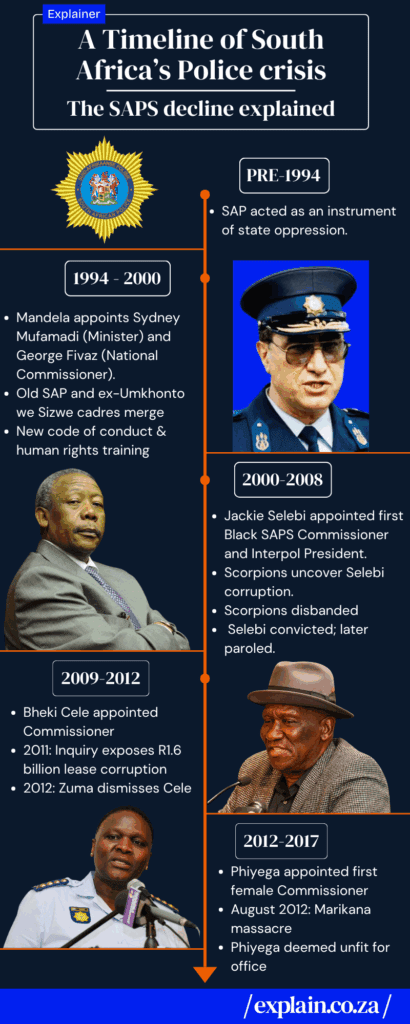

The apartheid hangover: 1994–2000

The SAPS did not emerge in a vacuum. Under apartheid, the South African Police (SAP, as it was then) operated as instruments of state oppression, tasked with suppression, intimidation, and surveillance. That legacy didn’t vanish in 1994, and fast-forward to democracy, and that hangover lingers.

When Nelson Mandela’s government took the reins in 1994, the brief was clear: dismantle the apartheid beast and build a people’s police. Enter Safety and Security Minister Fholisani Sydney Mufamadi and his handpicked National Commissioner, George Fivaz – tasked with fusing the old SAP, homeland forces, and ex-Umkhonto we Sizwe cadres into one unified SAPS.

Fholisani Sydney Mufamadi, an ANC underground veteran, laid the legal framework for later reforms. George Fivaz, a career apartheid-era detective turned democrat, succeeded in a gargantuan task assigned to him by Mandela personally: merging eleven disparate, often antagonistic, apartheid-era policing agencies into a single, unified South African Police Service.

The pair also rolled out community policing forums, human rights training, and a new code of conduct. Sounds promising, right?

The issue was that transformation was underfunded and rushed. By 1995, the force had ballooned to 150,000 new applicants, but integration meant clashing cultures – liberation fighters rubbing shoulders with ex-oppressors.

By 2000, modest gains, like more diverse recruits, were overshadowed by persistent brutality complaints. It was a noble start, but without teeth (or budget), it couldn’t bite back against the old habits.

The Selebi scandal: 2000–2008

Then came Jackie Selebi, the golden boy. Appointed in 2000, he was the first black commissioner – a symbol of progress, even landing the Interpol presidency, the second ever African chair of the international police crime organisation. But beneath the shine? A web of sleaze. By 2005, the Scorpions (that elite anti-corruption unit, which later morphed into the Hawks) uncovered Selebi’s cosy chats with shady figures, like Glenn Agliotti, a convicted drug lord. Bribes, protection rackets, it was corruption on a platinum scale. Selebi was convicted in 2010, slapped with 15 years (later paroled on medical grounds), but the damage? Irreversible.

Worse, his downfall coincided with the 2008 disbanding of the Scorpions – a move decried as political payback after they probed ANC bigwigs like Jacob Zuma. Suddenly, the SAPS lost its internal watchdog, paving the way for impunity. Elite state capture had arrived: when the bosses are crooked, how can the rank-and-file stay straight?

Bheki Cele’s rocky first go: 2009–2012

Bheki Cele stepped in as Police commissioner in 2009, vowing a tough-on-crime reboot. Cele, a populist ex-MK guerrilla, flooded streets with showy visible-policing stunts but did little when it came to the unglamorous work of better professionalising and capacitating the SAPs. He famously urged officers to “shoot to kill” criminals, a remark he later denied.

Early wins included visible policing forces on the ground, but scandals soon piled up. A 2011 inquiry exposed Cele authorising dodgy R1.6 billion leases with Roux Property Group – inflated deals that screamed corruption. Cele was eventually dismissed by Zuma in 2012. (A 2019 court later reinstated him, but the stink lingered.)

Political meddling was rife here, too – Zuma’s allies allegedly shielded Cele to keep a loyalist in place. It set a pattern: leadership tainted by faction fights, eroding any shot at impartial reform.

Marikana: 2012–2017

Enter Riah Phiyega, a former HR banker with zero cop experience, hand-picked by Zuma the same afternoon as Cele’s dismissal. Phiyega was the first female commissioner – another milestone soured by tragedy. Just two months in, the Marikana massacre unfolded at Lonmin’s platinum mine. Striking miners, armed but desperate, faced off against SAPS. Officers fired 295 rounds, killing 34 and wounding 78. The Farlam Commission in 2015 ripped into the response: no warnings, ignored surrender offers, and lethal force without justification. Phiyega was deemed “unfit” for office in December 2016.

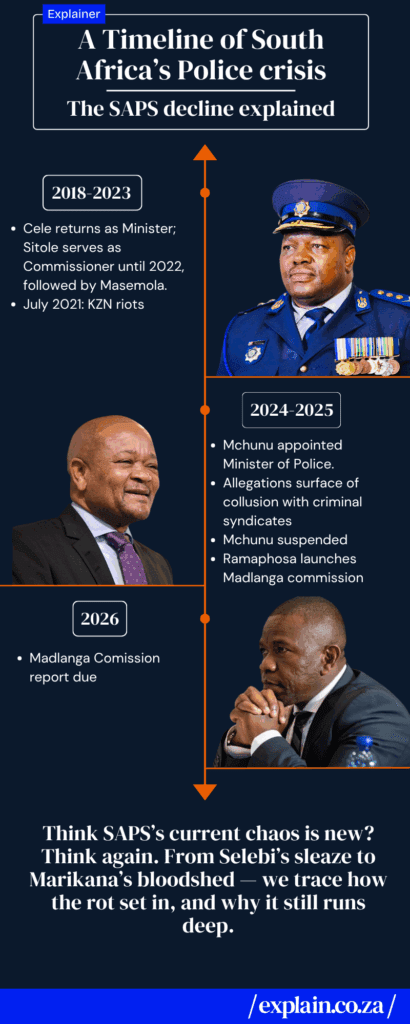

Cele’s return and the Sitole years: 2018–2025

Cele bounced back in 2018, this time as minister, with Khehla Sitole as commissioner until 2022, followed by Fannie Masemola. Ambitious plans for tech-driven policing and anti-gang units sounded good, but reality bit hard.

The July 2021 riots (sparked by Zuma’s jailing) laid bare the cracks: over 350 dead, billions in damage, and SAPS caught unprepared. Intelligence failures, delayed deployments, and poor coordination allowed looting to rage for days. The Human Rights Commission slammed it as a “failure of basic mandate,” with crime intel more focused on politics than public safety.

Under Masemola, efforts to professionalise continue, but corruption probes continue to persist. While Cele’s straight-talking style masked the reality of policing, woes like understaffing (roughly one officer per 430 citizens) continue.

The Mchunu mess: 2024–2025

Cue 2024: Senzo Mchunu, a Ramaphosa ally, gets the minister gig. But by July 2025, KwaZulu-Natal’s Nhlanhla Mkhwanazi drops a bombshell: Mchunu and Deputy Shadrack Sibiya allegedly colluded with syndicates, axing a task force probing political killings and burying evidence via WhatsApp whispers. Ramaphosa hits pause, suspending Mchunu and greenlighting the Madlanga Commission, chaired by retired Constitutional Court judge Mbuyiseli Madlanga, to probe the rot.

So, what’s the thread? And where do we go from here?

Pull it all together, and you see the patterns: apartheid’s authoritarian DNA, half-baked reforms, scandals, and politics treating SAPS like a personal fiefdom.

For many South Africans, the SAPS remains an institution they don’t trust, police who enforce rather than protect. And without trust, you cannot have effective policing.

That’s why the Madlanga Commission matters. It’s not just another inquiry into bad apples; it’s a chance to interrogate the system itself, to trace how power, politics and policing became so entangled.

But real reform won’t come from another commission or a change of leadership alone. The Madlanga Commission may be the latest in a long line of inquiries, but if it can finally force transparency within the force, it could be the first step toward a police service that protects, not polices, the people.

Emma is a freshly graduated Journalist from Stellenbosch University, who also holds an Honours in history. She joined the explain team, eager to provide thorough and truthful information and connect with her generation.

- Emma Solomon

- Emma Solomon