During his state of the nation address (Sona) last week, President Cyril Ramaphosa promised the social relief of distress grant (SRD) would be redesigned to “more effectively support livelihoods, skills development, work opportunities, and productive activity”. But the redesigned grant is delayed. The Department of Social Development said it planned to submit its revised basic income support (BIS) policy to Cabinet in March 2027.

Read our latest piece on what’s happening at Sassa here.

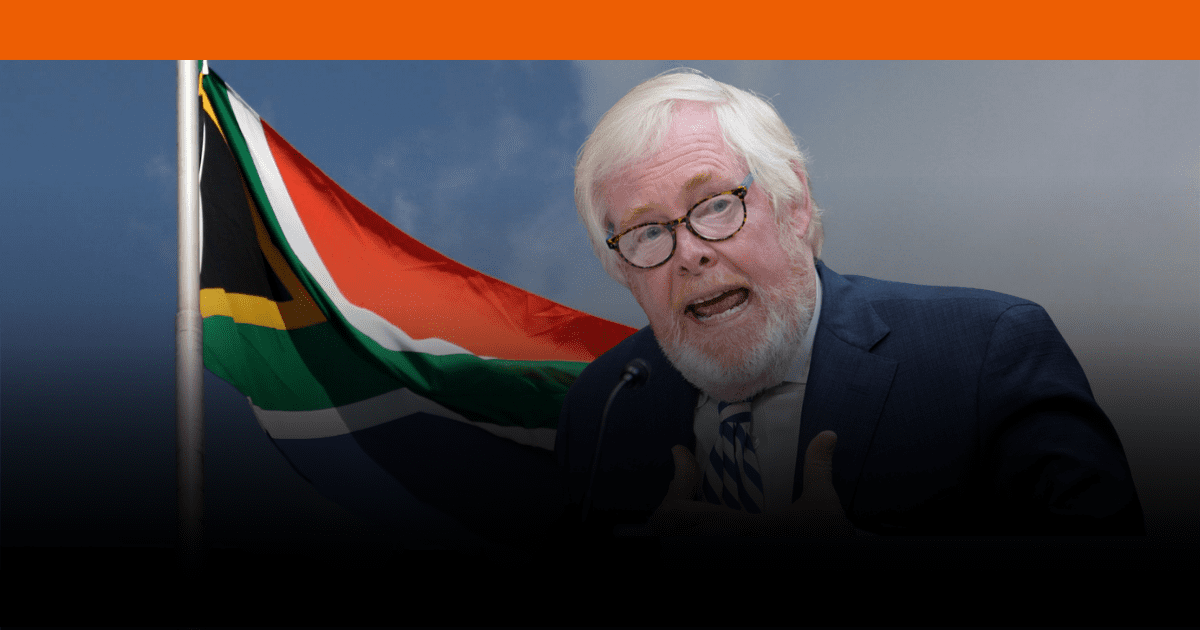

We know grants are a lifeline for many South Africans, so we spoke to Dr Khwezi Mabasa to find out more. He’s a lecturer and researcher who focuses on grants, and he answered some of our questions.

We all know a large number of South Africans rely on social grants – 19 million people to be exact (excluding the SRD grant) – but what role do they play in society?

- They provide a safety net

These grants actually help people to buy food and pay for transport. It’s been proven people also use the grants to support developing micro enterprises. The grants are an important cushion: people use them to support their livelihoods and for a variety of other purposes.

- They inject money into the economy

A lot of people think we can grow the economy just by giving people skills and by investing in manufacturing. This is important: we’ve got to grow skills, and we’ve got to build infrastructure. But we also need to have demand: people must have money to buy goods. When people are unemployed, at least the grants give them money to buy goods. That’s important for economic growth.

- They support people doing care work

A lot of unemployed citizens are engaged in care work. They look after kids, and sick or elderly people in their households. They cook and clean their houses. People who are able-bodied and older than 18 don’t get paid for that labour. Grants are an important way for people to be paid for this work.

What’s missing from the government’s approach to grants?

The issue is that the government thinks that if people are able-bodied, older than 18, and younger than 65, they don’t need social security. That’s wrong: they actually do need social security. People are not unemployed by choice. This is why the social relief of distress (SRD) grant is important.

The SRD grant was introduced during the Covid pandemic in 2020 to help vulnerable people. It has since been extended, with the aim of ultimately providing a BIS.

People are unemployed because we have a history of socioeconomic inequality. This makes it difficult for them to participate in the labour market. We know inequality makes it tricky for people to access resources. The government needs to understand that we have to continue with the SRD grant and make it a universal basic income grant.

Speaking of the basic income grant, what are some of the major roadblocks to its implementation?

In most countries, the government makes a decision, and the finance department follows those plans. In our case, it’s the opposite. The government and departments make a decision, but they have to go to the Treasury, which will do a cost-benefit analysis.

The problem is some people have the wrong idea about unemployment: they say grants will make people lazy and not look for jobs. I find that quite problematic: it assumes the only reason people don’t have jobs is that they don’t work hard enough or are too lazy to acquire the necessary skills.

We know that’s not the case. Our education system is not up to scratch, our skills system is not up to scratch, and some people live in areas where there’s little development or investment.

How has income support worked in other places? Tell us more about Brazil’s Bolsa Família programme.

Brazil has a social security programme called the Bolsa Família. It is similar to a grant. But the difference is they give people coupons. If you get the grant, you have to spend it at local retailers. That’s important because the grant isn’t just about the cash transfer: it’s about changing the economy.

Right now, people in South Africa take the money out – let’s say it’s at a Sassa office or Checkers or Pick n Pay. But then they’re spending money in the same shops. So we’re not changing the structure of the economy. Most people spend money on food. Imagine if you tie the grant to rebuilding local food systems.

The crucial thing about the Brazil programme is that people who get the grant have to play their own part. So they have to make sure their children go to school and are vaccinated. They have to make sure they’re in a skills or training programme.

Instead of saying the grant is too costly, the attitude should be: how do you link it to other areas of human development so that you can use it to improve the livelihoods of South Africans?.

But what about the cost factor?

There’s this idea that we don’t have enough money to fund the grants, which just doesn’t make sense.

What we do know in South Africa is that we can use other mechanisms to finance the grant. For example, we can increase corporate tax. South Africa’s corporate tax has been going down for a very long time. In 1999, it was 35% – today it’s 27%. The idea was that decreasing it would bring more investment, lead to growth, and create more jobs. That hasn’t happened.

The second thing is that we have to stop wasteful expenditure in government, so we can direct money towards the grants.

What would you say to critics of social grants and the welfare state?

In countries that have expansive welfare systems, like Finland and Norway, there’s a direct relationship between spending on welfare and improved human development outcomes. This is in areas such as education, decent employment, productivity, and skills. So you need social security to produce these human-development outcomes.

Welfare is not only about looking after people: it’s about developing the economy. So if you use welfare in a circular way, you spend the money, it goes into the economy, it creates jobs, and it creates productivity.

This is probably the most important one. If you see welfare as a way of changing the structure of the economy, you can use it to change the food and transport systems.

A welfare state isn’t an anti-developmental state. It’s actually all about building a developmental state – if you design it properly.

The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.