Picture this: it’s August 2025, and a leaked poll from the Democratic Alliance (DA) hits the headlines like a thunderbolt. The African National Congress (ANC), the party that’s dominated South African politics since the end of apartheid, is shown dipping below 30% national support for the first time ever – clocking in at just 29%, with the DA hot on their heels at 28%. Not only that, but the poll suggests the DA is surging ahead in key metros like Tshwane and eThekwini, painting a picture of potential urban upheaval.

Well, no need to imagine, that’s what’s currently happening.

Headlines quickly framed it as a watershed moment: the ANC, for the first time, was polling in the twenties. Commentators asked if this was the endgame for the governing party. WhatsApp groups buzzed with speculation: was the DA really surging? Could it even overtake the ANC before the next local elections?

But before anyone starts drafting coalition agreements, let’s take a step back.

Polls are complicated beasts. A political poll is a survey of a sample of voters designed to estimate how the broader population might vote, using statistical methods to reflect demographics and voter behaviour.

Some are snapshots worth paying attention to. Others, especially those commissioned by political parties, need to be read with a very large pinch of salt.

So, what does this leaked poll actually tell us? Is this a sign of the ANC’s empire crumbling, or just a snapshot in a very fluid political game?

And, perhaps more importantly, how can we tell which polls to trust in South Africa’s unpredictable political landscape?

Why do local elections and their polls matter?

First off, those elections are looming larger than you might think. They’re set to happen sometime between 2 November 2026 and 31 January 2027, marking the end of the current five-year term for municipal councils.

Unlike national elections, these are where voters get really personal — punishing or rewarding parties based on everyday gripes like dodgy water supply, pothole-riddled roads, or flickering streetlights.

With a staggering 472 parties potentially on the ballot, including disruptors like the uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) Party and the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF), expect a lot of fragmented results leading to even more coalitions.

Why is this poll shaking the ANC?

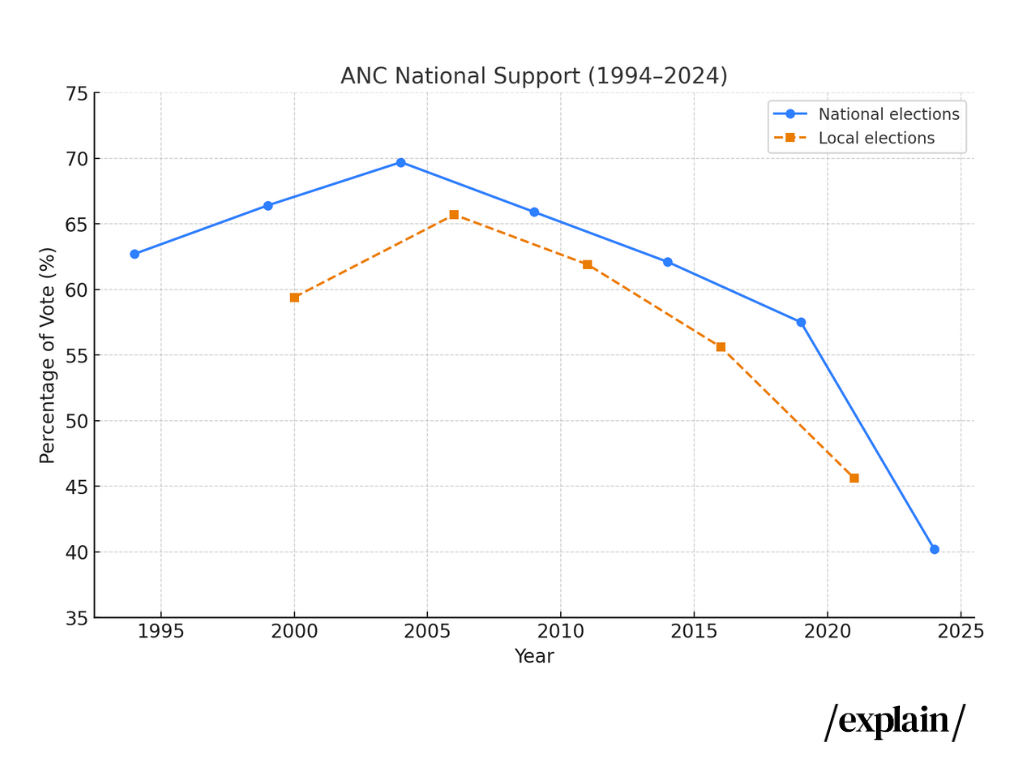

Symbolism matters. Seeing the ANC in the twenties feels like a collapse for a party that won nearly 70% in 2004. The leaked DA poll suggested the DA was virtually neck-and-neck with the ANC in metros like Tshwane and eThekwini, with smaller parties such as the EFF and uMkhonto weSizwe (MK) not far behind.

But elections analyst Wayne Sussman cautions against over-interpreting. “We are a long way out from the election. In fact, the election might only take place in January 2027,” he told explain. “A lot can change between now and then.”

He notes that ANC support often dips between elections, only for the party to claw back ground closer to voting day. “Of course there’s a chance they could fall below 30%, but whether they fall well below remains to be seen. There are still parts of Johannesburg and elsewhere where ANC support is sticky and somewhat resolute.”

Paul Berkowitz, another election analyst, agrees: “We should take the dip seriously but not necessarily focus on the number. Voter sentiment can change a lot over the next 14 months. There has been a decline in ANC support since the 2024 election — I’m just not sure it’s as much as ten percentage points.”

What the numbers say — and don’t say

So why the caution? It comes down to how polls are done.

Pollsters don’t ask the whole population how they’ll vote — they interview a sample and try to ensure it reflects South Africa’s demographics. The DA’s leaked poll reportedly surveyed 1,820 voters, which is in line with many political polls. But sample size alone doesn’t tell the whole story.

What really matters is the margin of error (MoE). This is the “give or take” that shows how far off the result could be. The DA’s poll had an 8% margin of error in metros like Johannesburg.

Berkowitz explains why this matters: “You’d like to aim for at most a 4% margin of error. An 8% MoE means you could adjust the ANC or DA up or down eight percentage points and the new scenario would be just as statistically likely. In Johannesburg, you could take the DA down from 40% to 32%, and bump the ANC from 23% to 31%. Suddenly, instead of a 17-point lead, they’re neck-and-neck.”

That’s why Helen Zille, the DA’s federal chair, dismissed the leak as misleading. She admitted the numbers were real but said they were never meant to be read as hard predictions. Party polls are internal tools, taken frequently to gauge mood and momentum, not to forecast elections years in advance.

Does it matter if it’s a party or an independent poll?

Another key issue: who commissions the poll.

Sussman says it’s important to look at methodology rather than simply dismissing a party poll. “I wouldn’t dismiss the poll outright because it’s by the DA or an opposition party. [The DA] polls consistently.” The trick is to look at the sample size, the turnout assumptions, and whether the results match broader trends.

That last point matters. Independent polls this year — such as those by the Institute of Race Relations (IRR) and the Social Research Foundation (SRF) — also show ANC support sliding.

An April IRR poll put the DA at 30.3% and the ANC at 29.7%, marking the first time in their data series that the DA has polled ahead. Another independent source, the SRF, had the ANC around 32%, the DA around 25%, and about 15% of voters undecided

Party-commissioned polls also tend to underplay smaller parties. Berkowitz warns: “Smaller parties are underrepresented, particularly in our voting system which favours many smaller parties.”

How do turnout assumptions affect polls?

Perhaps the most important caveat is turnout modelling. The DA poll assumed a 100% national turnout. That is pure fantasy. South Africa hasn’t seen turnout above 80% since 1999, even in the most contested national elections. In the 2021 local polls, turnout was just 45%.

Why does this matter? Because different turnout levels favour different parties. Berkowitz breaks it down: “In the DA poll, the metros are modelled for voter turnout of 56%, which is probably very close to the actual turnout. The national results are modelled for 100% turnout, which is never going to happen. Different levels of turnout tend to favour different parties; historically the DA has done better with lower overall turnout and the ANC has done better with higher turnout.”

In other words, assuming everyone votes is an easy oversight when looking at election polling.

What does this signal signal about voter behaviour?

Even with the caveats, both analysts agree the ANC is vulnerable heading into 2026/27. “Right now, voters are less happy with the ANC and happier with the DA than last year,” Berkowitz said. “There is a real risk to the ANC that the DA will overtake it in most of the metro municipalities.”

But local elections are notoriously tricky to predict. Voters tend to use them as a “reality check” — punishing or rewarding councillors based on water supply, rubbish collection, or broken streetlights. That makes local polls harder to model than national elections.

Sussman notes another wrinkle: Coalition politics is here to stay. “We are on a trajectory that many municipalities will be run by coalitions. Even more will be under coalition control in 2026. Right now we have three metropolitan area municipalities, Cape Town, Buffalo City and Mangaung, which are the only metros not run by coalitions. It will remain to be seen as that stays.”

That instability means national mood swings don’t always map neatly onto municipal outcomes. In some towns, strong local parties or civic movements can suddenly upset the balance. Think of Team Sugar South Africa in KwaZulu-Natal or the Namakwa Civic Movement in the Northern Cape.

So, should we believe the hype?

To ANC critics, it’s proof that the party is collapsing. To DA supporters, it’s evidence of real momentum. To sceptics, it’s just one snapshot, distorted by methodology and turnout assumptions.

The truth lies somewhere in between. Independent polls like the IRR and SRF back up the broader trend: the ANC is declining, the DA is gaining, and smaller parties like MK are making the landscape more unpredictable. But no single poll — least of all one leaked from a party’s war room — can tell us what will happen in 2026/27.

As Sussman puts it: “Polling adds to our political discourse.” It’s useful, but it’s always just a snapshot.

The ANC may yet bounce back, the DA may consolidate its surge, or new wildcards may emerge. With more than a year to go — and turnout, coalitions, and local issues all in play — South Africans would be wise to treat every poll as a conversation starter, not a crystal ball.

Emma is a freshly graduated Journalist from Stellenbosch University, who also holds an Honours in history. She joined the explain team, eager to provide thorough and truthful information and connect with her generation.