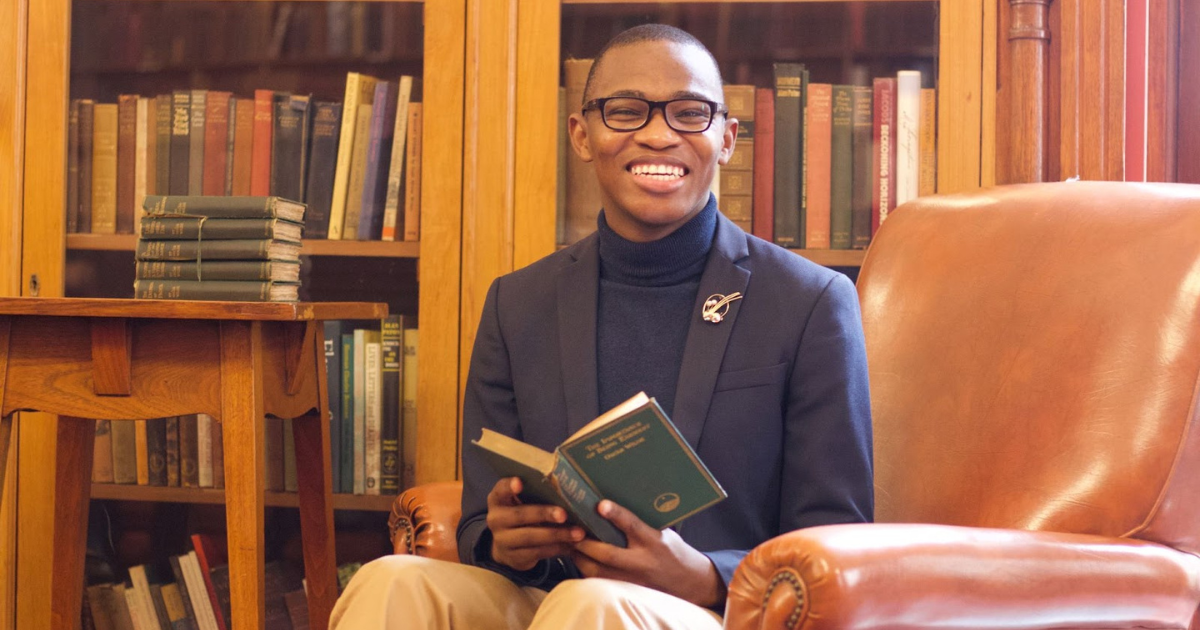

Lucky Dinake isn’t your stereotypical South African politician—and he’s proud of it.

“People don’t necessarily think of a 160-centimetre little gay man at 30 years old who became Chief Whip at 29,” he says with a self-aware laugh.

But in many ways, Dinake is emblematic of a generation trying to reinvent the political wheel—young South Africans who are less interested in the old combative style of politics and more concerned with cooperation, equity and delivering real change at the local level.

As the Chief Whip of the Official Opposition (Democratic Alliance) in the City of Ekurhuleni, Dinake’s work is equal parts administration, policy oversight, relationship management, and good old-fashioned people skills. “Everything the light touches is my job,” he jokes.

A calling rooted in service

Dinake grew up in Germiston in a family steeped in service. “We were not wildly privileged in any way,” he says. “But one thing we were always raised with was a sense of responsibility for the world we live in.” His parents worked with disabled communities, and his siblings are active in policing, churches, and charity organisations.

That sense of duty led Dinake to study HIV/AIDS counselling and later coaching. “My calling has been making the world better through conversation,” he says. “Creating space for people to talk and engage.”

It was a community lunch that introduced him to politics—a chance encounter with then-local councillor Michéle Clark, now a member of Parliament. He describes it as “a bad joke that went too far”—but quickly realised that politics could be a powerful tool for impact.

He was accepted into the DA Young Leaders Programme in 2014, calling it “a finishing school for leaders under 35.” Since then, he’s held almost every conceivable leadership role within the party before being elected councillor in 2016.

What does the ‘94 generation fight for today?

Dinake was born in 1994, the year South Africa entered democracy. He sees his political mission as part of a generational shift.

“Our generation’s concern is no longer apartheid,” he says. “It’s the fact that no matter which neighbourhood you live in, you probably won’t have electricity for five days out of two weeks. It’s graduates who are unemployed because our economy can’t sustain jobs. It’s access to healthcare that’s practically useless.”

He warns that clinging too tightly to liberation-era identities risks becoming irrelevant. “If your identity is exclusively rooted in a context that no longer exists, then you risk becoming politically out of touch.”

What’s needed instead, he argues, is a model of politics built on collaboration, particularly in today’s coalition-heavy local governments. “We have to model a politics that works harder to get people on the same page than to advance a totally different book.”

What does a Chief Whip actually do?

If you think local politics is small-scale, think again. As Chief Whip, Dinake is essentially the Chief Operating Officer of his caucus.

He manages everything from caucus discipline and committee assignments to policy advice and media releases. He’s responsible for internal conflict resolution and external stakeholder management—“like if two councillors are at each other’s throats, I step in,” he says.

And yes, all correspondence between the DA and other branches of government? That too. “Everything the light touches is my job,” he reiterates.

He’s also trying to redefine what the job can be, particularly in coalition settings. As the DA representative on the multi-party whips forum, Dinake has made a conscious effort to pilot cooperation over combative politics. “Some things have to be sacred,” he says. “They have to transcend party lines. Things like fairness. Things like the equitable allocation of resources.”

Despite the high-pressure role, Dinake is adamant that politicians must stay grounded and connected. “One can’t be divorced from the reality that people go through. I have no electricity at home today—it’s day two. I’ve packed a bag and gone to a friend’s house just to shower.”

He spends time each week in his constituency, covering three wards in Katlehong. “We have to put the city first. Not just the people who voted for us—all residents. When services stop because politicians are bickering, it’s the people who suffer.”

On youth, activism and the power of showing up

For Dinake, being a young politician isn’t about optics—it’s about representation. “We need to carve out space for ourselves. We can’t keep letting people who are old enough to be our parents tell our stories.”

His message to young people is simple but urgent: “Nobody’s going to do it for you. Get involved and pay attention.”

He adds, “There’s a fine line between victims and volunteers. If we don’t show up, we leave a vacuum. And then it’s filled by people who don’t speak for us.”

The ballet boardroom and arts as activism

In a delightful twist, Dinake also serves as co-chair of the South African International Ballet Competition board—his “other life,” as he puts it. He became involved after befriending dancers from Joburg Ballet and realising he could bring his arts management and political skills to the table.

It’s a role he takes seriously. Under his tenure, the competition has introduced regional events in underfunded provinces and worked to bring coherence to a fragmented ballet community. “The arts are the one thing that can bridge all our divides,” he says.

He’s passionate about expanding arts access, especially in Ekurhuleni. “We have theatres sitting empty. We need to reframe the value of arts in our society. Our performers are worth it.”

Staying grounded in chaos

How does he cope with the chaos of local politics? Dinake carves out time for himself—horse riding twice a week (“you can’t think about anything else when controlling a 500kg animal”), quarterly retreats in the Midlands, and quality time with his four beloved nieces. “They are the light of my life. Being their uncle is my favourite job.”

He credits his team—especially his staff in the Office of the Chief Whip—for making his role possible. “It’s the hardest job in politics. I couldn’t do it without them.”

A politics of community

In the end, Dinake sees both his political and arts work as part of the same mission: building communities. “Community is probably how we’re going to fix our country. We need a whole-of-society approach.”

It’s a vision rooted not in bluster or ideology, but in service and shared responsibility. As he puts it: “We have to choose who we want to be—and then we have to be that.”

Emma is a freshly graduated Journalist from Stellenbosch University, who also holds an Honours in history. She joined the explain team, eager to provide thorough and truthful information and connect with her generation.