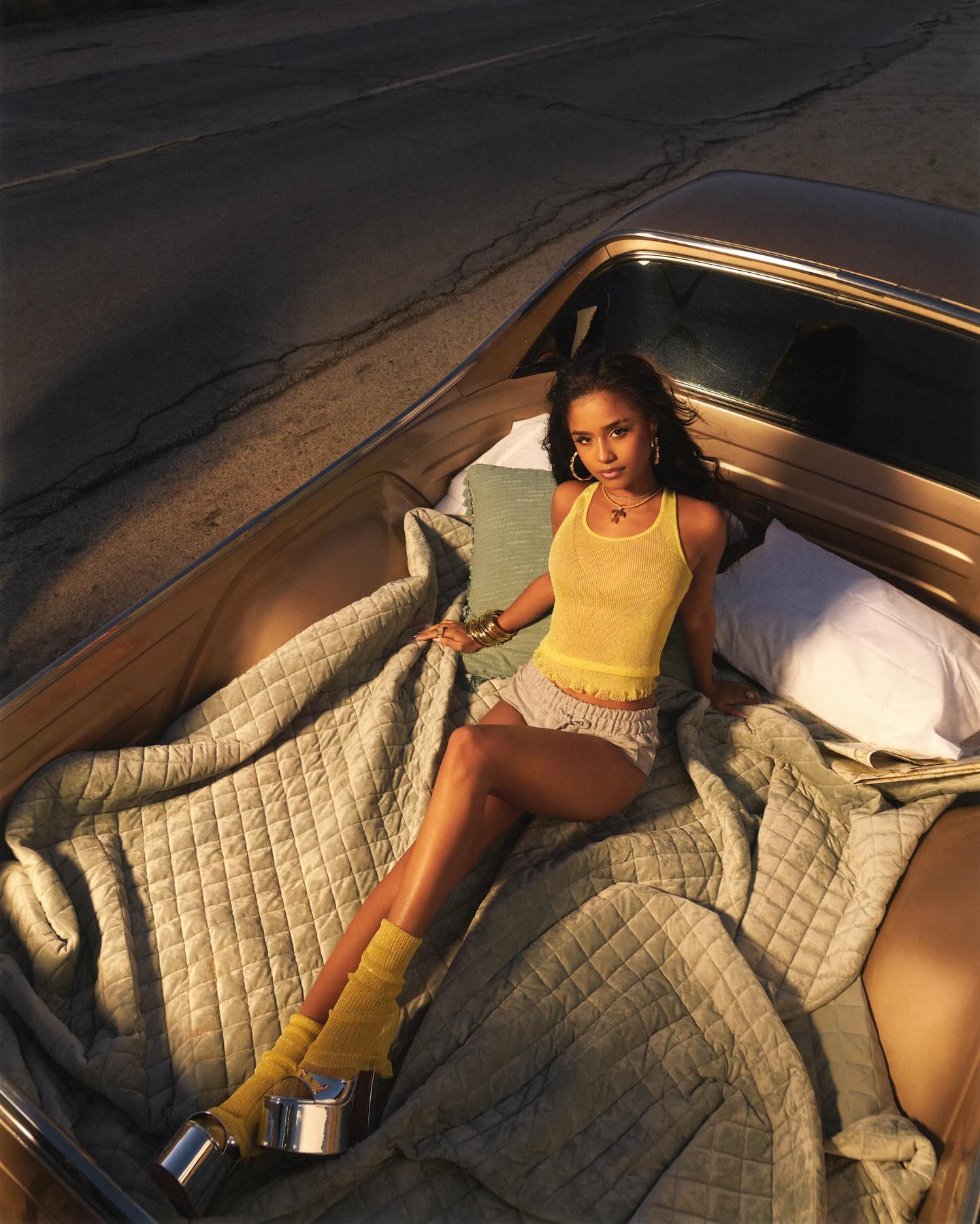

Image accreditation: hector_cbs (flickr.com)

Music is a universal language. Everyone has a song that they like from all sorts of genres. One wonders if those Paleolithic humans knew what their crude instruments – often rattles, shakers and drums – would bring forth.

It’s not precisely clear when music evolved in the Paleolithic era. Heck, we’re not even sure if other human cousins except Homo Neanderthelisis made music with any meaning. Music predates speech in its very basic form.

If one thing has put South Africa on the world map, it’s our music. South Africa has always had a firm grip on the global music scene, from Makeba to Black Coffee.

A brief history of music in South Africa

Let’s take a quick trip through South Africa’s musical history. In the Dutch colonial days, local tribes and enslaved folks mixed Western instruments with their own, creating unique sounds. In the 1800s, coloured bands in Cape Town, influenced by British military tunes, blended regional folk music with Western instruments.

Fast forward to the 1930s, and we’ve got radio for Black listeners, boosting indigenous recordings and spreading Zulu a cappella singing. Solomon Linda’s “Mbube” in 1939 set the stage for isicathamiya. Then, the 1950s brought Kwela, putting South African music on the international radar.

Sophiatown in the ’50s was this hub mixing Marabi, Zulu Indlamu, and American swing, fostering a cool cultural exchange. But in the ’60s, apartheid ended Sophiatown, scattering musicians. The ’70s saw Ladysmith Black Mambazo hitting the global stage, and the ’80s gave rise to Afro-jazz, followed by the ’90s kwaito scene.

From Kwaito to The Yanos

“In its infancy, Kwaito was a rebellion. The world was making electronic dance music, and young South African creatives didn’t relate to the music. Kwaito was a voice for the youth,” says Monde Mtyolo, a DJ and music expert based in Johannesburg, South Africa. I spoke to him about the role music has played in South Africa.

Mtyolo mentions how the kind of music being released at that time narrated the shift from apartheid to the new-found freedom, aspirations, opportunities, love and heartache, celebrations and the residual effects of the new and developing political landscape. “Songs like Arthur Mafokate’s ‘Kaffir’ are most likely the representation of the early days of Kwaito. The song addressed a malicious White boss (a baas) for using the racist slur ‘Kaffir’ towards a young Black man who only wants to hustle and make a better life for himself,” he said.

We’re seeing a similar move with Amapiano, says Mtyolo. Amapiano is a South African subgenre of house music that emerged in South Africa in the mid-2010s. It combines deep house, jazz, and lounge music, characterised by synths and expansive percussive basslines. In its origins, it was characterised by live piano players on stage.

The sound evolved rapidly and differently around Gauteng, with Pretoria, Ekurhuleni and Soweto having their movements with their distinct sounds. “Again, what makes Amapiano stand out is its authentic mirroring of society. The songs talk about everything experienced by a young South African, ranging from love and heartbreak, aspirations and optimism to how South Africans celebrate life. Much like Kwaito, Amapiano has become a lifestyle influencing how young people dance, what they consume, how they look, what they wear and where they should be,” he said.

South Africa has a unique history with House music, including its evolution in the townships during the 1980s. House music in South Africa was officially brought to the forefront with the release of a compilation called Fresh House Flava in 1998 through House Afrika Records, says Mtyolo. “It is a known fact that House Music comes from the underground Chicago ‘warehouse’ scene where young queer Black kids snuck off into abandoned warehouses for a safe space where they could be themselves.

DJs such as Frankie Knuckles and Larry Heard led the movement and would edit disco songs to make them fit into their desired moulds,” he said. The genre then exploded worldwide, with South African DJs purchasing these rare records to play during the Kwaito era. In 2002, the twins and DJ/production duo Revolution released a self-produced album, ‘The Journey.’ Soon after, South African DJs transitioned into producers and released their works. “House and Kwaito have since coexisted and crossed paths. They have been the building blocks for sounds that emerged since, such as Gqom and Amapiano,” Mtyolo concluded.

In the rhythm of time, South Africa’s musical saga unfolds like a melody of resilience, rebellion, and celebration. From haunting indigenous music to the vibrant beats of Amapiano, the nation has harmonised its history through music. As the dance of societal narratives continues, one thing is for sure – South Africa’s music will keep echoing across borders, transcending language and connecting hearts in its universal groove. Let the music play.

Tshego is a writer and law student from Pretoria. A keen follower of social media trends, his interests include high fantasy media, politics, science, talk radio, reading and listening to music.

He is also probably one of the only people left who still play Pokemon Go.